This week we'll learn about the Straddle's first cousin, the Strangle. Let's start off with a definition.

Definition: A long (short) Strangle is the purchase (sale) of an out of the money (OTM) Put and an OTM Call on the same underlying stock with the same time to expiration. There's also a similar strategy, called a Guts, where both of the options are ITM.

With XYZ stock trading at $50, an example of a long Strangle would be the purchase of the XYZ July 45 Put and the July 55 Call. If the Call is trading for $1.25, the Put for $.90 and we bought 10 Strangles, the total cost (excluding commissions) would be $2,150. Of course, if we sold the Strangles, we would receive a credit for that same amount coming into our account. Like the Straddles, long Strangles must be paid for in full; they cannot be bought on margin. Short Strangles have margin requirements that will be discussed in a future article.

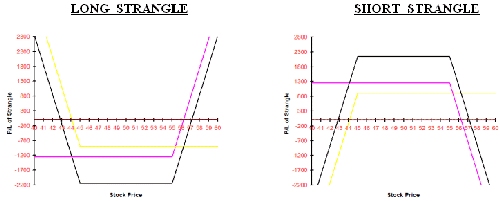

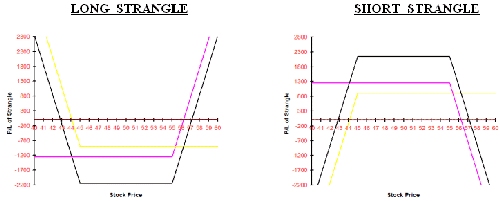

The following graphs show the profit and loss for both long and short Strangles at expiration, using the pricing discussed above. Notice, that as you would expect, they are mirror images of each other. If one side makes money, the other side loses the same amount. Like I said last week, it's a zero sum game.

Notes: The black lines represent the Straddle positions. The purple and yellow lines represent the expiration graphs of the Call and Put, respectively.

Like the Straddle, the Strangle is a strategy to be used when we expect the stock to make a large move, but we're not sure in which direction the movement will take place. This can happen when an event is expected, such as earnings, a verdict in a court case, an FDA announcement, etc. There can also be unexpected events, such as a takeover, merger, announcement of a new product, or the replacement of a key officer of the company, etc., that will cause the stock to make a large move.

So why would I use the Strangle instead of the Straddle? For one, it's a lot cheaper. The 10 XYZ 45/55 Strangles cost $2,150. Using a theoretical options calculator and the same variables used to calculate the Strangle prices, I calculated that 10 XYZ 50 Straddles would cost $5,800 ($3 for the Call and $2.80 for the Put.) Of course, there's a trade-off, at expiration, the breakeven stock prices for the Straddle are $44.20 and $55.80, whereas for the Strangle the breakevens are at $42.85 and $57.15. Obviously, from this perspective we want a greater move when we put on a Strangle.

If you remember the graph of the long Straddle, it looks like a V, with the point at the strike price. That would be the worst place for the stock to be at expiration because it would result in the loss of the entire premium. Movement in either direction away from the strike would be beneficial to the position. However, with the Strangle, the maximum loss at expiration occurs over the full range from the low strike price to the high strike. In the above example and graph, the entire premium would be lost if the stock closed between $45 and $55 at expiration. In fact, you might feel more comfortable with the other side of the trade, the short Strangle, since it makes the maximum profit (which is $2,150) over the same range, $45-$55. The problem with this trade is that there is significant risk on the downside, and unlimited risk on the upside. In a future article I'll discuss ways of mitigating that risk.

Like we did for the Straddle, let's examine the characteristics of this spread in terms of the Greeks. I'll talk about the long Straddle, but you know that the short side will be just the opposite.

Note: Some of the comments relating to the Greeks are the same or very similar for the Straddle and the Strangle. Rather than have you go back to the Straddle article, I've essentially repeated the information with minor modifications as needed.

DELTA and GAMMA - Assuming that the Strangle was put on with the stock price close to the middle of the range of the strike prices, the delta will be close to 0, approximately +30 for the Call and -30 for the Put. That means that the position doesn't have a bias to either the upside or the downside. However, since the position is long the Call and the Put, and since both Calls and Puts have positive Gamma, the Strangle is long Gamma. (Not as long as the Straddle would be since both options are OTM and we know that the ATM options have the maximum amount of Gamma.) This Gamma position will cause the Strangle to get shorter on the downside and longer on the upside. That will be useful if we are trying to keep the delta of the position close to 0 because it will require the purchase of stock when the price is low and the sale of stock when the price is high.

Like I said above, the worst case scenario is for the stock at expiration to finish in between the range of the strike prices since that would result in the loss of the entire premium. But like the Straddle, in reality, we would have either exited the position prior to expiration or made adjustments along the way, and most probably would not have lost the entire amount. That process will be discussed in a future article.

VEGA - Since the position is long options and long options have positive Vega, this position is sensitive to changes in volatility, although not as much so as the Straddle. (The reason being that the OTM options have less Vega than the ATM options.) So in addition to price movement, we are hoping for an increase in volatility. Well, that implies that we would put this position on in a low volatility environment. Isn't that the same contradiction we had with the Straddle? We want a low volatility environment, but large movement in the stock! Yes and no; at expiration the volatility doesn't matter anymore. The stock price will be whatever it is, and that will determine the amount of profit or loss for the position. Prior to expiration, the volatility can have a great impact on the value of the Strangle.

THETA - Once again, we're still dealing with only long options, and long options have negative theta, so the position is losing value every day. Making matters worse, the rate of loss is constantly accelerating. So what can we do to mitigate this situation? We generally don't buy near term Strangles. Like the Straddle, a rule of thumb is that Strangle buys should be 3 months or more to expiration. I said "generally" for a reason.

As you can see, the long Strangle can be a very effective tool and can ring in some large profits, but more than anything else you need movement in the stock price. Since the maximum risk is defined, I consider this a low risk, low probability trade, but with a high percentage return when it is profitable. Experts will continue to debate the advantages and disadvantages of the Strangle relative to the Straddle but most traders will come to feel comfortable with one or the other. For what it's worth, since I am basically a volatility trader I tend to do many more Straddles than Strangles. But then again, each one of you will have to develop your own style. Unfortunately, there's no textbook answer.

Definition: A long (short) Strangle is the purchase (sale) of an out of the money (OTM) Put and an OTM Call on the same underlying stock with the same time to expiration. There's also a similar strategy, called a Guts, where both of the options are ITM.

With XYZ stock trading at $50, an example of a long Strangle would be the purchase of the XYZ July 45 Put and the July 55 Call. If the Call is trading for $1.25, the Put for $.90 and we bought 10 Strangles, the total cost (excluding commissions) would be $2,150. Of course, if we sold the Strangles, we would receive a credit for that same amount coming into our account. Like the Straddles, long Strangles must be paid for in full; they cannot be bought on margin. Short Strangles have margin requirements that will be discussed in a future article.

The following graphs show the profit and loss for both long and short Strangles at expiration, using the pricing discussed above. Notice, that as you would expect, they are mirror images of each other. If one side makes money, the other side loses the same amount. Like I said last week, it's a zero sum game.

Notes: The black lines represent the Straddle positions. The purple and yellow lines represent the expiration graphs of the Call and Put, respectively.

Like the Straddle, the Strangle is a strategy to be used when we expect the stock to make a large move, but we're not sure in which direction the movement will take place. This can happen when an event is expected, such as earnings, a verdict in a court case, an FDA announcement, etc. There can also be unexpected events, such as a takeover, merger, announcement of a new product, or the replacement of a key officer of the company, etc., that will cause the stock to make a large move.

So why would I use the Strangle instead of the Straddle? For one, it's a lot cheaper. The 10 XYZ 45/55 Strangles cost $2,150. Using a theoretical options calculator and the same variables used to calculate the Strangle prices, I calculated that 10 XYZ 50 Straddles would cost $5,800 ($3 for the Call and $2.80 for the Put.) Of course, there's a trade-off, at expiration, the breakeven stock prices for the Straddle are $44.20 and $55.80, whereas for the Strangle the breakevens are at $42.85 and $57.15. Obviously, from this perspective we want a greater move when we put on a Strangle.

If you remember the graph of the long Straddle, it looks like a V, with the point at the strike price. That would be the worst place for the stock to be at expiration because it would result in the loss of the entire premium. Movement in either direction away from the strike would be beneficial to the position. However, with the Strangle, the maximum loss at expiration occurs over the full range from the low strike price to the high strike. In the above example and graph, the entire premium would be lost if the stock closed between $45 and $55 at expiration. In fact, you might feel more comfortable with the other side of the trade, the short Strangle, since it makes the maximum profit (which is $2,150) over the same range, $45-$55. The problem with this trade is that there is significant risk on the downside, and unlimited risk on the upside. In a future article I'll discuss ways of mitigating that risk.

Like we did for the Straddle, let's examine the characteristics of this spread in terms of the Greeks. I'll talk about the long Straddle, but you know that the short side will be just the opposite.

Note: Some of the comments relating to the Greeks are the same or very similar for the Straddle and the Strangle. Rather than have you go back to the Straddle article, I've essentially repeated the information with minor modifications as needed.

DELTA and GAMMA - Assuming that the Strangle was put on with the stock price close to the middle of the range of the strike prices, the delta will be close to 0, approximately +30 for the Call and -30 for the Put. That means that the position doesn't have a bias to either the upside or the downside. However, since the position is long the Call and the Put, and since both Calls and Puts have positive Gamma, the Strangle is long Gamma. (Not as long as the Straddle would be since both options are OTM and we know that the ATM options have the maximum amount of Gamma.) This Gamma position will cause the Strangle to get shorter on the downside and longer on the upside. That will be useful if we are trying to keep the delta of the position close to 0 because it will require the purchase of stock when the price is low and the sale of stock when the price is high.

Like I said above, the worst case scenario is for the stock at expiration to finish in between the range of the strike prices since that would result in the loss of the entire premium. But like the Straddle, in reality, we would have either exited the position prior to expiration or made adjustments along the way, and most probably would not have lost the entire amount. That process will be discussed in a future article.

VEGA - Since the position is long options and long options have positive Vega, this position is sensitive to changes in volatility, although not as much so as the Straddle. (The reason being that the OTM options have less Vega than the ATM options.) So in addition to price movement, we are hoping for an increase in volatility. Well, that implies that we would put this position on in a low volatility environment. Isn't that the same contradiction we had with the Straddle? We want a low volatility environment, but large movement in the stock! Yes and no; at expiration the volatility doesn't matter anymore. The stock price will be whatever it is, and that will determine the amount of profit or loss for the position. Prior to expiration, the volatility can have a great impact on the value of the Strangle.

THETA - Once again, we're still dealing with only long options, and long options have negative theta, so the position is losing value every day. Making matters worse, the rate of loss is constantly accelerating. So what can we do to mitigate this situation? We generally don't buy near term Strangles. Like the Straddle, a rule of thumb is that Strangle buys should be 3 months or more to expiration. I said "generally" for a reason.

As you can see, the long Strangle can be a very effective tool and can ring in some large profits, but more than anything else you need movement in the stock price. Since the maximum risk is defined, I consider this a low risk, low probability trade, but with a high percentage return when it is profitable. Experts will continue to debate the advantages and disadvantages of the Strangle relative to the Straddle but most traders will come to feel comfortable with one or the other. For what it's worth, since I am basically a volatility trader I tend to do many more Straddles than Strangles. But then again, each one of you will have to develop your own style. Unfortunately, there's no textbook answer.

Last edited by a moderator: