In what has become a fairly regular event and taking a past example from a few years ago, a Wall Street firm announced in May 2012 a multibillion-dollar trading loss. JPMorgan told analysts and investors in early May that year that a hedge trade they had made would lead to a loss of at least $2 billion. CEO Jamie Dimon said that the firm "screwed up" and a number of mistakes allowed the loss to occur. He said that the trades were "riskier, more volatile, and less effective as an economic hedge than we thought." Individual traders face the same challenges with trades that don't always behave as expected and they generally use a number of techniques to minimize the chance of a large loss.

Individual traders have different motivations than institutional traders. Often, the individual is trying to make sure they have enough money for retirement or they may even depend on trading profits as their primary source of income.

In contrast, institutional traders have a base salary to cover their monthly expenses, and benefits often include a well-funded retirement plan. For them, trading increases their bonuses, which means they would be more aggressive than individual traders. Because of this, institutional traders may not use the simple risk management tools that an individual would.

FIVE SIMPLE RULES TO MANAGE RISK

Most individual traders diversify their investments, although this may not be possible for those trading smaller accounts. Even when diversification is impossible, the individual uses other risk management strategies to ensure their trading survival.

In the JPMorgan trade, the trader seemed to be concentrating his bets in a single derivatives market. In a Bloomberg News story about the loss, the wire service noted that it "first reported April 5 that [the trader in London at the center of the problem] had built positions that were so large he was driving price moves in the $10 trillion market for credit-swap indexes."

Later reports indicated that a large portion of the trade involved a single credit default swap contract. That the trader was moving the price against his position indicates that his position size was probably too large. Of course, the size of the loss also indicates the position size was too large, so we can immediately draw three important lessons from the JPMorgan trade:

- Diversification across markets helps reduce risk.

If a trader is betting on a single market and the market moves against them, a large loss can easily result.

- Trade only the most liquid markets.

Small traders could move a market against their position in illiquid stocks or thinly traded options markets. Some futures markets are also so thinly traded that small traders using market orders could create a significant price move. This is especially true in contracts with more distant expiration dates.

- Keep the position size small enough to avoid catastrophic losses.

If a trader has a $1,000 account and is using 100% of the available margin in a stock trade, it would take a loss of 50% to wipe out their position. That same account size with a position in the futures market leveraged at 20 to 1 could be wiped out with a 5% move. Managing leverage helps reduce the chance of a catastrophic loss. Other risk management strategies include using stop-losses. Many traders enter a stop when they open a trade. Other traders believe that stop-losses can hurt profitability, a concern that has proven true in many systems that are backtested. However, even traders who consider stops to be harmful to profits often enter a stop far away from the market price, perhaps 20% to 25% away, to avoid losses that can end their trading careers. That provides the fourth lesson from the JPMorgan trade:

- Use stops to avoid the risk of ruin.

With or without stops, individual traders usually limit their potential losses with position sizing. Large traders may only put 2% of their trading capital at risk on any trade. Smaller traders may need to risk a third to a half of their account size in order to accommodate the average trading range in their market. By using this risk management strategy, stop-loss orders can be eliminated, and that could give more trades time to work. If only 5% of capital is risked in a trade, it would take about 130 consecutive losses to lose 99% of the beginning capital. That is another lesson:

- Position size can be used as a strategy to limit risks.

These simple rules seem to have been overlooked by JPMorgan and Lehman Brothers before that, and Bear Stearns before that. There are other examples of hedge funds that ignored these simple ideas and blew up.

COMPLEX FORMULAS DEFINE RISK

Institutional traders prefer ideas like value at risk (VAR) to define their risk rather than calculating how much they can lose by summing the difference between the market price and their stop-loss for each open position. Value at risk is a more complex calculation and firms use different variations of the calculation, but one way to find VAR is given with this formula:

VAR = (µ + z * σ) * P

Where VAR = Value at risk

µ = Mean returns over a given time frame

z = Left tail risk assuming a normal distribution

σ = Standard deviation of returns

P = Portfolio value

The result is the maximum dollar amount that they can expect to lose 95% of the time. Individual traders understand that the gains on losses on the most extreme 5% of trading days can account for the bulk of a trader's results in a year, yet VAR ignores this idea and defines risk in terms of what can happen on a normal day.

The problems with VAR have long been known. During the subprime crisis that sparked the bear market in 2007, Goldman Sach's CFO was quoted as saying, "We were seeing things that were 25-standard deviation moves, several days in a row."

It is difficult to comprehend how infrequent a 25-standard deviation event would be expected to occur. An eight-standard deviation event would be expected about once in 6.5 trillion years. But market selloffs happen much more frequently than that and there almost always seem to be at least a few very bad days within a short time span every year.

In the reality of trading, losses will exceed the VAR calculation fairly frequently if you are using two standard deviations in a VAR model. A two-standard deviation event should be expected about once every two months (once every 44 trading days), so traders will frequently see days when their account value changes by an amount that is more than VAR calculated.

There are assumptions built into the VAR and different assumptions can give different results. In the $2 billion loss, JPMorgan has said that the traders making the bet believed that the VAR was about $67 million, but a different model that the firm used showed that the VAR was actually $129 million. Dimon concluded that the method used for calculating VAR was "inadequate."

A SIMPLER CALCULATION FOR INDIVIDUAL TRADERS

Individual traders may not want to model VAR, but they can determine how much money is at risk under normal conditions by applying Bollinger Bands to their account value. To find a rough equivalent of VAR:

- Track account values on a daily or weekly basis.

- Find the standard deviation of the account balances. Twenty days or weeks can work, although longer time frames may be more useful, since markets do not follow a normal distribution. Ideally, at least a year's data would be available.

- Multiply the standard deviation by two. This is the dollar amount at risk under normal market conditions.

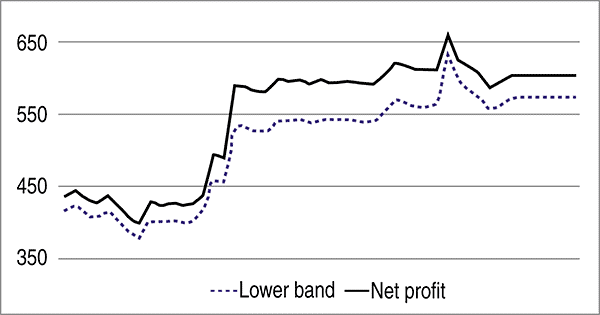

An example of this is shown in Fig 1, where, in effect, a lower Bollinger Band has been added to the system's trading account balance. A simple four-week channel breakout system trading a basket of commodities was used to generate account values, which can also be called an equity curve. The dollar amount at risk varies with the account balance and the recent trading performance. The lower band in this example is calculated using a 20-week look-back period.

Fig 1: EQUIVALENT OF VALUE AT RISK (VAR).

Here, a lower Bollinger Band has been added to the system's trading account balance. The lower band in this example is calculated using a 20-week look-back period.

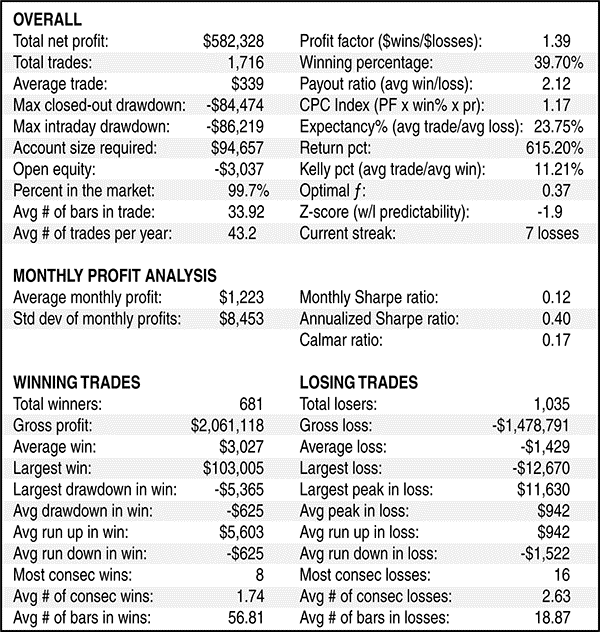

A typical system trading report for this channel system, generated with Trade Navigator software and data, is shown in Fig 2.

Fig 2: SIMPLE STRATEGY.

This simple strategy (buy new 4-week highs and sell new 4-week lows) is profitable over time. This back test covered a period of about 40 years.

The worst loss in any month on a dollar basis exceeded the lower Bollinger Band only twice in the 460-month testing period. That means every month, it is relatively simple to obtain a number comparable to VAR at the 95% confidence level by applying Bollinger Bands to actual account performance. Gains exceeded the upper band significantly more often, almost 6.5% of the time.

One reason to complete these calculations is to understand the "normal" potential losses of your system. By finding two standard deviations of your equity curve, you can turn losses from a theoretical figure to a defined dollar amount. If that amount makes you uncomfortable, change the system to reduce the risk. If the level of risk seems too small, you can become more aggressive.

This concept also introduces the idea of applying technical analysis to your equity curve. Consider adding a moving average to the equity curve. A 30-period moving average works well, although any other time period can be used. No system will always be in synch with the market. When the equity curve is below the moving average, that is a signal that the system is out of synch, and putting that system aside until the equity curve is back above the moving average can help avoid large losses.

EXPERIENCE IS THE BEST TEACHER

Experience is the best teacher, but in the markets, experience can often be the most expensive teacher. It is far less expensive to learn from the mistakes of others than it is to learn by making each mistake yourself.

Individual traders can learn important lessons from JPMorgan's multibillion-dollar loss. There are a number of simple lessons regarding risk management and there is also the idea of regularly examining your trading performance with an analysis of your equity curve. The lessons learned from this loss could be valuable to individual traders, especially those who could not survive a $2 billion loss.

Michael Carr can be contacted on this link: Michael Carr