In one of those "it was all I could do not to actually pinch myself" moments, I had the great pleasure of interviewing former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan last week in front of a "small" audience of 3,000. The event was IMPACT, Schwab Institutional's annual conference, and Greenspan was the opening keynote speaker. He prefers a Q&A format over a speech, and I jumped at the chance to have a "conversation" with him last Monday morning. Some of the most interesting aspects to the conversation were not on stage, but behind the "curtain" in the green room.

Green room redirect

In the green room, after initial pleasantries with Greenspan and our own Chuck Schwab, the first question asked was by Greenspan to me: "Please don't tell me you're going to ask a bunch of softball questions! Can we talk about the hard stuff?" That was music to my ears, but I did let him know that there were a list of questions his staff had provided that gave guidelines about what could be addressed. After he gently scolded his accompanying staff for using a "too fluffy" list of questions, we sat down to talk about what was really on his mind.

He immediately suggested we devote ample time to the housing market, including the subject of non-traditional mortgages. I asked whether we could delve into the impact of hedge funds and exotic derivatives on the market, and he said, "Absolutely." I asked whether I could bring up the recent comments made by Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher, who has suggested the Fed lowered rates too far and held them down too long based on faulty inflation information. He gave the thumbs up on that one. Finally, I asked if I could inquire as to mistakes he thought he made over his 18½ years at the Fed's helm, and he said that was fair game, too. So, we headed onstage, me blissfully without the boundaries of the original questions.

Emancipation proclamation

I did start with a bit of a softball question, but one I knew the audience would have asked, too. We all wanted to know, after 18½ years as the most important figure in the global economy, what it was like to be a "free man" in the private sector. He gave us a big smile and said it was very "liberating," especially his ability to speak more openly than before. And that set the stage for his answers yet to come.

Haves vs. have-nots

I asked another general question about the state of the U.S. economy, to which Greenspan replied, "Not bad." He predicted a continued weakening into early next year, but said he's confident "the worst is behind us" since profit margins are high and capital orders are potent. "We have been in a slowing period, but it's temporary," he said. "The global economy is in extraordinarily good shape." What does worry him is the concentration of income, creating a widening gap between the haves and the have-nots that could possibly result in governments returning to protectionist policies. "While the global economy is stressful, the alternative is far worse." For what it's worth, he expressed grave concerns about increased protectionism in the green room before we went onstage.

Social Security's 15-minute solution

Another topic about which he expressed considerable distress was entitlement spending, especially Medicare. "I'm very concerned about long-term fiscal policy," he said. But, if politicians would just put aside their partisan leanings, it would take policymakers only "15 minutes" to come up with a solution for Social Security, and 10 of those minutes would be "spent exchanging pleasantries," he joked (to great laughter and head-nodding). Calling the fiscal policy on Medicare "irresponsible," Greenspan explained that although we know the number of recipients for benefits, we have no clue as to the average payment amount. He expressed fear that the U.S. government will continue to promise benefits it may not be able to deliver. "This is a serious fiscal issue that can't be helped by increasing taxes," he said.

Economic white elephant - housing

We swiftly moved to the one economic white elephant - housing. Although it's "too soon to say" if we're close to the bottom of the housing bust, Greenspan doesn't predict a rapid decline. I did get the sense that he was back-pedaling a bit from his well-quoted view recently that housing may have hit bottom. In fact, I reminded him that his "irrational exuberance" comment in 1996 came over three years prior to the market's ultimate top in 2000. In his well-crafted reply, he suggested, "This is not the bottom, but the worst is behind us." My skepticism about a muted impact of housing on the broad economy is well-documented, so I wasn't fully in agreement when he went on to say that housing market activity is likely no longer to be a drag on overall economic growth as unsold inventories clear out and stabilize against sales levels.

I followed up by asking about the rash of non-traditional mortgages that characterized this housing boom/bust. He replied that those "flaky" exotic mortgages, which allowed consumers to purchase homes more expensive than they could afford, will be financially devastating for those families holding them, but will have little impact on the macro economy. Again, I hope he's right, but I have my doubts.

Pollinating bees

But, exotic isn't all bad in the mind of the Maestro, as he's often been called. Greenspan called exotic derivatives, and their hedge fund architects, "pollinating bees" and "extraordinarily important" to a complex global economy, since their high rates of return help stabilize the entire economic system and offset our meager savings rate.

Toughest decision(s)

When I asked Greenspan to relate his toughest decisions during his years as Fed Chairman, he said he didn't recall any decision as being particularly tough, although he admitted that "tranquility was not my state of mind" when faced with the market crash of October 19, 1987. Instead, he described economic decision-making as relatively straightforward. "There was no [economic] event that we didn't know what to do about," he said. "What we didn't know was how it was going to turn out."

The week prior to my conversation with Greenspan, Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher said in a speech that the fed funds rate was cut to a level that "turned out to be lower than what was deemed appropriate at the time, and was held lower longer than it should have been." The Fed's policy "amplified speculative activity in the housing and other markets," Fisher said. Now, he added, the correction in the housing market is "inflicting real costs to millions of homeowners across the country" and complicating the Fed's task of containing inflation. Greenspan disputed such criticism, saying the recent housing boom resulted not from Fed cuts of short-term rates, but rather from global financial conditions that lowered long-term rates worldwide. "In retrospect, I know of nothing we would have done differently," Greenspan said confidently of policy during those years.

The long and short of it

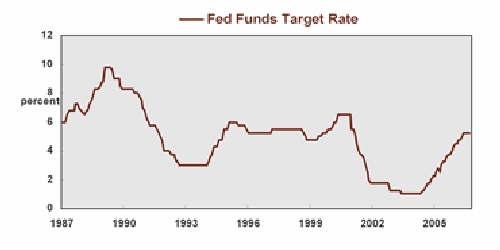

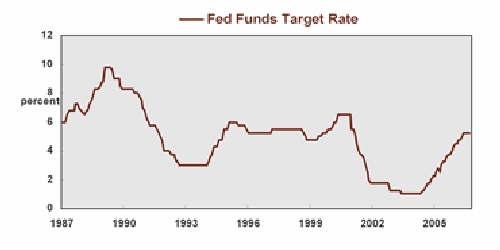

As you can see in the two charts below, there were numerous short-rate cycles over which Greenspan presided, including the major downturn in rates prompted by the 1991 recession, the gradual tightening brought on by the 1990s economic boom, the swift retreat unleashed by the post-bubble bear market earlier this decade, and finally the removal of much of that ease during his last months in office.

caption: Short rates' ups and downs

Sources: Bloomberg and FactSet. As of October 31, 2006.

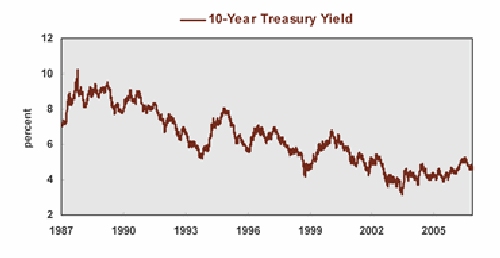

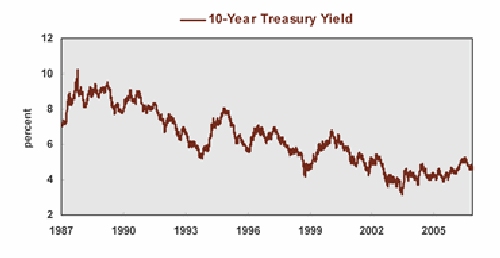

But short-rates are only part of the story as can be seen in the chart below, which shows the more consistently downward sloping line of longer-term interest rates. Greenspan once famously described the phenomenon of stubbornly low long-term interest rates, despite the Fed's recent steady increases in short-term benchmark rates, as a "conundrum." He conceded in our discussion that his job was made a bit easier over his 18½ years given the long down cycle in rates that followed the high-inflation era of the 1970s and early 1980s, and as mentioned above brought on the housing boom.

caption: Long rates' long down cycle

Source: Bloomberg. As of November 10, 2006.

What we all really wanted to know!

I couldn't resist my final question. While he was Chairman, the media often scrutinized the size of his briefcase for clues as to whether the Fed would raise or lower interest rates. So, I asked whether there was any validity to those claims. "Not at all," answered Greenspan. "Whether my briefcase was fat or thin depended on whether or not my wife made me lunch that day."

Green room redirect

In the green room, after initial pleasantries with Greenspan and our own Chuck Schwab, the first question asked was by Greenspan to me: "Please don't tell me you're going to ask a bunch of softball questions! Can we talk about the hard stuff?" That was music to my ears, but I did let him know that there were a list of questions his staff had provided that gave guidelines about what could be addressed. After he gently scolded his accompanying staff for using a "too fluffy" list of questions, we sat down to talk about what was really on his mind.

He immediately suggested we devote ample time to the housing market, including the subject of non-traditional mortgages. I asked whether we could delve into the impact of hedge funds and exotic derivatives on the market, and he said, "Absolutely." I asked whether I could bring up the recent comments made by Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher, who has suggested the Fed lowered rates too far and held them down too long based on faulty inflation information. He gave the thumbs up on that one. Finally, I asked if I could inquire as to mistakes he thought he made over his 18½ years at the Fed's helm, and he said that was fair game, too. So, we headed onstage, me blissfully without the boundaries of the original questions.

Emancipation proclamation

I did start with a bit of a softball question, but one I knew the audience would have asked, too. We all wanted to know, after 18½ years as the most important figure in the global economy, what it was like to be a "free man" in the private sector. He gave us a big smile and said it was very "liberating," especially his ability to speak more openly than before. And that set the stage for his answers yet to come.

Haves vs. have-nots

I asked another general question about the state of the U.S. economy, to which Greenspan replied, "Not bad." He predicted a continued weakening into early next year, but said he's confident "the worst is behind us" since profit margins are high and capital orders are potent. "We have been in a slowing period, but it's temporary," he said. "The global economy is in extraordinarily good shape." What does worry him is the concentration of income, creating a widening gap between the haves and the have-nots that could possibly result in governments returning to protectionist policies. "While the global economy is stressful, the alternative is far worse." For what it's worth, he expressed grave concerns about increased protectionism in the green room before we went onstage.

Social Security's 15-minute solution

Another topic about which he expressed considerable distress was entitlement spending, especially Medicare. "I'm very concerned about long-term fiscal policy," he said. But, if politicians would just put aside their partisan leanings, it would take policymakers only "15 minutes" to come up with a solution for Social Security, and 10 of those minutes would be "spent exchanging pleasantries," he joked (to great laughter and head-nodding). Calling the fiscal policy on Medicare "irresponsible," Greenspan explained that although we know the number of recipients for benefits, we have no clue as to the average payment amount. He expressed fear that the U.S. government will continue to promise benefits it may not be able to deliver. "This is a serious fiscal issue that can't be helped by increasing taxes," he said.

Economic white elephant - housing

We swiftly moved to the one economic white elephant - housing. Although it's "too soon to say" if we're close to the bottom of the housing bust, Greenspan doesn't predict a rapid decline. I did get the sense that he was back-pedaling a bit from his well-quoted view recently that housing may have hit bottom. In fact, I reminded him that his "irrational exuberance" comment in 1996 came over three years prior to the market's ultimate top in 2000. In his well-crafted reply, he suggested, "This is not the bottom, but the worst is behind us." My skepticism about a muted impact of housing on the broad economy is well-documented, so I wasn't fully in agreement when he went on to say that housing market activity is likely no longer to be a drag on overall economic growth as unsold inventories clear out and stabilize against sales levels.

I followed up by asking about the rash of non-traditional mortgages that characterized this housing boom/bust. He replied that those "flaky" exotic mortgages, which allowed consumers to purchase homes more expensive than they could afford, will be financially devastating for those families holding them, but will have little impact on the macro economy. Again, I hope he's right, but I have my doubts.

Pollinating bees

But, exotic isn't all bad in the mind of the Maestro, as he's often been called. Greenspan called exotic derivatives, and their hedge fund architects, "pollinating bees" and "extraordinarily important" to a complex global economy, since their high rates of return help stabilize the entire economic system and offset our meager savings rate.

Toughest decision(s)

When I asked Greenspan to relate his toughest decisions during his years as Fed Chairman, he said he didn't recall any decision as being particularly tough, although he admitted that "tranquility was not my state of mind" when faced with the market crash of October 19, 1987. Instead, he described economic decision-making as relatively straightforward. "There was no [economic] event that we didn't know what to do about," he said. "What we didn't know was how it was going to turn out."

The week prior to my conversation with Greenspan, Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher said in a speech that the fed funds rate was cut to a level that "turned out to be lower than what was deemed appropriate at the time, and was held lower longer than it should have been." The Fed's policy "amplified speculative activity in the housing and other markets," Fisher said. Now, he added, the correction in the housing market is "inflicting real costs to millions of homeowners across the country" and complicating the Fed's task of containing inflation. Greenspan disputed such criticism, saying the recent housing boom resulted not from Fed cuts of short-term rates, but rather from global financial conditions that lowered long-term rates worldwide. "In retrospect, I know of nothing we would have done differently," Greenspan said confidently of policy during those years.

The long and short of it

As you can see in the two charts below, there were numerous short-rate cycles over which Greenspan presided, including the major downturn in rates prompted by the 1991 recession, the gradual tightening brought on by the 1990s economic boom, the swift retreat unleashed by the post-bubble bear market earlier this decade, and finally the removal of much of that ease during his last months in office.

caption: Short rates' ups and downs

Sources: Bloomberg and FactSet. As of October 31, 2006.

But short-rates are only part of the story as can be seen in the chart below, which shows the more consistently downward sloping line of longer-term interest rates. Greenspan once famously described the phenomenon of stubbornly low long-term interest rates, despite the Fed's recent steady increases in short-term benchmark rates, as a "conundrum." He conceded in our discussion that his job was made a bit easier over his 18½ years given the long down cycle in rates that followed the high-inflation era of the 1970s and early 1980s, and as mentioned above brought on the housing boom.

caption: Long rates' long down cycle

Source: Bloomberg. As of November 10, 2006.

What we all really wanted to know!

I couldn't resist my final question. While he was Chairman, the media often scrutinized the size of his briefcase for clues as to whether the Fed would raise or lower interest rates. So, I asked whether there was any validity to those claims. "Not at all," answered Greenspan. "Whether my briefcase was fat or thin depended on whether or not my wife made me lunch that day."

Last edited by a moderator: